- Mobility

- Pastoralism

- Relational values

- Indigenous Peoples (IP) – also IPLCs

- One Health: people, livestock rangelands

- Culture, cultural continuity, sense of identity

(return to DN homepage)

Where does the term ‘nomad’ come from?

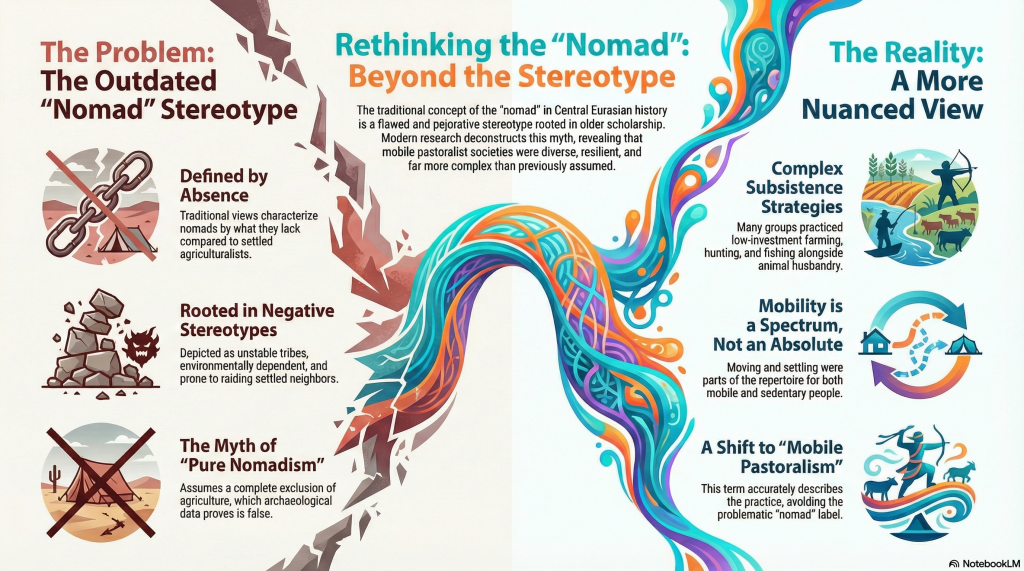

Excerpts, Deconstructing the concept of the ‘nomad’ in Central Eurasia (Conte, 2025)

“The term ‘nomad’ can be traced back to the ancient Greek verb nemein, ‘to pasture, distribute or graze flocks’ (Montanari 1995: 1340), from which the substantive nomos, ‘wandering in search of pasture’, is derived (Dal Zovo 2015: 211).

“While nemein emphasises animal husbandry, nomás introduces the mobile aspect, which defines our contemporary understanding of ‘nomad’ – a person who leads a residentially mobile existence (Barnard and Wendrich 2008: 3–5).

“In academic and non-academic contemporary usage, ‘nomad’ suggests the image of poor, yet somewhat noble, vagabonds. [...] What is often referred to as nomadism should rather be called mobile pastoralism and can be defined as the co-occurrence of pastoralism and mobility (Honeychurch 2015: 57). Many scholars have attempted a clear definition of nomadism to be used internationally and cross-disciplinarily but have failed because of the term’s conceptual weakness (Cribb 1991: 68; Bar-Yosef and Khazanov 1992: 2; Schlee 2005: 23–25).

“[Often times] pejorative representations conflate mobile people, their subsistence mode – mobile pastoralism – and the steppe environment into one immutable entity, and obscure the very diversity of mobile pastoralism and people who practise it. [...] Ultimately, the concept of the nomad proves to be a paradox which should be abandoned in favour of more relational definitions and approaches.”

Infographic by NotebookLM

Mobility

Excerpts, Deconstructing the concept of the ‘nomad’ in Central Eurasia (Conte, 2025)

“Mobility refers to the capacity and need to move, and is measured through factors such as distance covered, frequency of movement and segment of the population involved (Barnard and Wendrich 2008: 5; Schlee 2005: 17). The degree of mobility is said to regulate the continuum between sedentism and nomadism, but mobility has multiple forms, such as individual, group and residential mobility (Meadow 1992: 262). Mobility is largely, but not exclusively, motivated by the availability of resources, which influence stationary periods, varying from a few hours or nights to several years (Barnard and Wendrich 2006: 6). So how mobile must a ‘real nomad’ be (Honeychurch 2015: 54)? Mobility cannot simply be viewed on a sliding scale between sedentary and mobile, as both moving and settling is part of the repertoire of sedentary and nomadic people (Schlee 2005: 22–23).”

Pastoralism

Excerpts, Deconstructing the concept of the ‘nomad’ in Central Eurasia (Conte, 2025)

“Pastoralism can be characterised as ‘mobile and extensive animal husbandry not necessarily divergent from agriculture’ (Bar-Yosef and Khazanov 1992: 2). So-called pure nomadism, or nomadic pastoralism, is defined by the exclusion of agriculture and, by extension, sedentism (Meadow 1992: 262). The term semi-nomadism is used when a portion of the population is settled, or the whole population is settled for a period of the year (Barnard and Wendrich 2008: 7). While the practice of agriculture clearly influences a group’s mobility, assuming people are tied to the seasonality of crops (Bar-Yosef and Khazanov 1992: 2), this definition of nomadic pastoralism is being revised. Recent studies have revealed that many fully nomadic communities in fact practised low-investment agriculture. In some Scythian groups, a part of the population was settled all year round and practised agriculture (Spengler et al. 2021: 253). With the deconstruction of the hunting-agriculture-pastoralism framework and increasing evidence for multi-subsistence strategies, complementary activities such as hunting and fishing are also being considered (Honeychurch and Makarewicz 2016: 349–50).

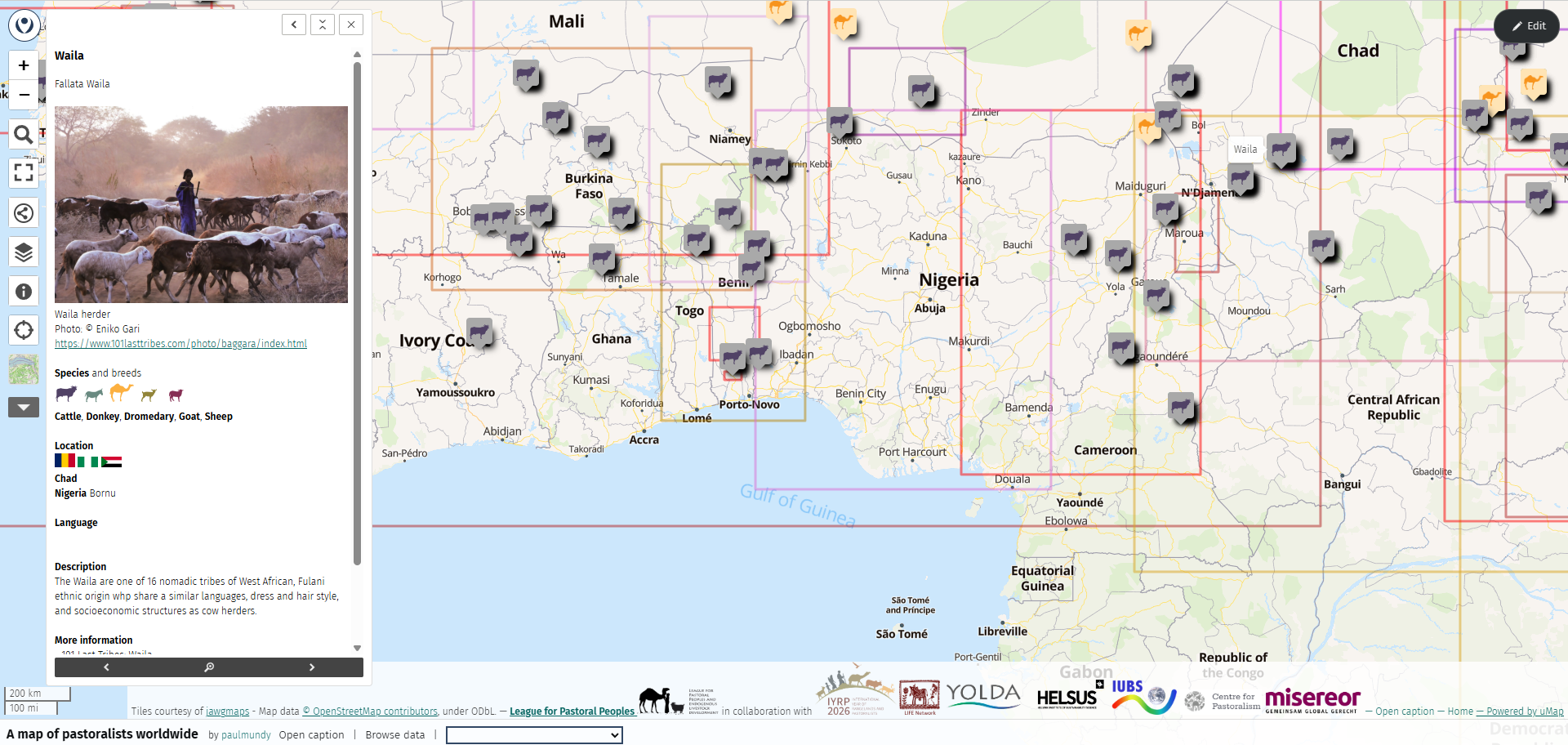

- Interactive map of 1000+ pastoralist people groups worldwide

Relational values

Three types of values: Instrumental (or utilitarian), intrinsic (or inherent), and relational

1

2

Indigenous Peoples (IP) – also IPLCs

1

2

One Health: people, livestock rangelands

1

2

Culture, cultural continuity, sense of identity

1

2